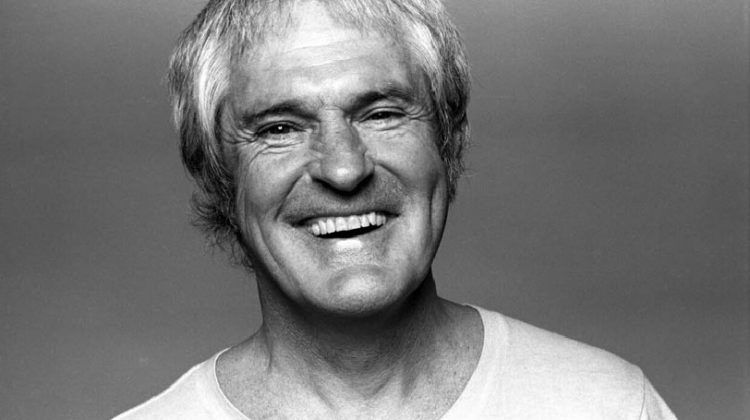

In this month’s Dose of Science, instead of focusing on a specific scientific paper, we present a biography of Dr Timothy Leary, the controversial psychedelic pioneer. Before he became the messiah of sixties’ counterculture, Leary was a professor of psychology at Harvard. In this piece, we trace his journey from straight academic to prophet of the psychedelic era.

Leary was born on October 20, 1920, in Springfield, Massachusetts, the son of Irish immigrants. He liked to say that he was conceived on January 17th of that year, the first day of alcohol prohibition. After high school, he first studied at the Westwood military academy, but quickly figured out that the military was not for him. Next, he wanted to study philosophy at the University of Alabama; a chance encounter, however, with the school’s leading psychologist, Dr Dee, convinced him to study psychology instead. After graduating, he studied further to obtain a PhD. His dissertation was focussed on psychometry, the science of the measure of personality traits.

In 1957, Leary left for a long European holiday to process the suicide of his first wife. During this trip, his first book was published, and received very favorable reviews from the scientific community. As a result he was offered a position at Harvard, which he accepted in the autumn of 1959. Even his Harvard colleagues considered him exceptionally bright, and all the signs pointed to his having a long and successful academic career. This plan quickly went astray.

In the summer of 1960, Leary took a holiday in Mexico with his family and friends. During a conversation, someone mentioned that shamans in the nearby villages cultivated magic mushrooms. Leary had heard of the mystical mushrooms, without being particularly interested; now that an opportunity had presented itself, however, he decided to take the bait. On August 9, while he was sipping a cold Coronita beer, the mushrooms kicked in: Leary noticed how everything was full of life, and he had a personal vision of evolution, experiencing the four-billion-year history of life on Earth from a personal perspective. Later in life, he often said that he learned more about the human psyche during these few hours than during fifteen years of academic studies.

Right after Leary returned from his holiday, he founded the famous Harvard Psychedelic Project. The project initially focused on volunteers taking psilocybin in a controlled environment. The volunteers had to fill out questionnaires at various timepoints after the experience. Leary and his organisation subsequently used this data as a basis for studying the short-, mid- and long-term effects of psilocybin. In general, reactions were very encouraging: all the participants spoke of overwhelmingly positive experiences and a feeling of being reborn.

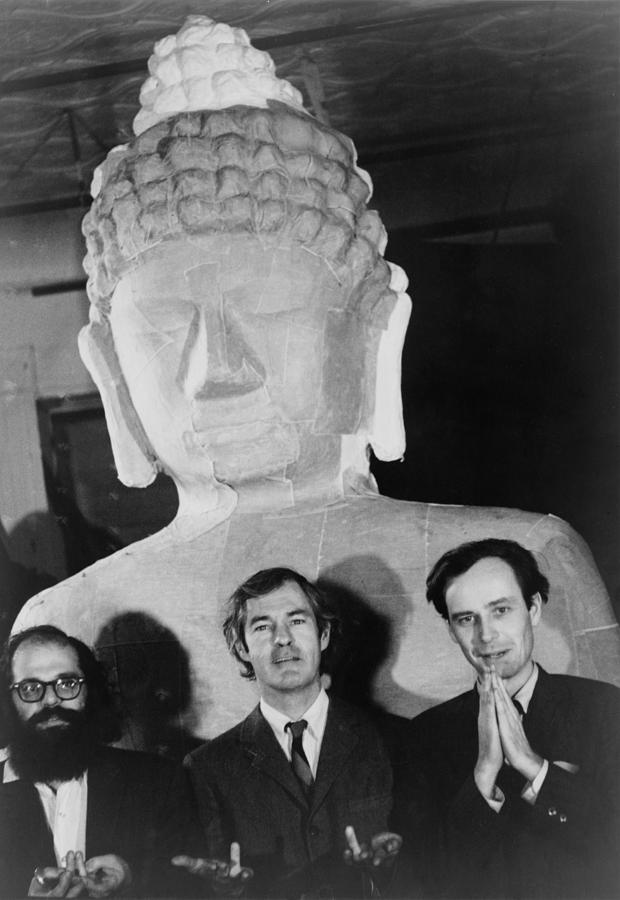

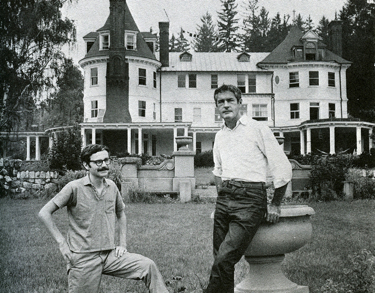

Leary with one his psychedelic colleagues (Ralph Metzner)

While the subjective reports looked great, in order to gain scientific credibility, Leary needed something more than questionnaires to prove the value of psilocybin He needed an objective measure to show the potential of the substance. To this end, he conducted his famous Concord Prison experiment. In Leary’s time, about 70% of inmates quickly found their way back to prison after release. Obviously, the high recidivism rates seemed to defeat the whole purpose of a prison system. Leary organised it so that selected inmates were able to participate in psilocybin-assisted therapy. Leary’s hypothesis was that remission rates would be significantly lower among the group of inmates who had participated in his psilocybin-assisted therapy. The therapy seemed a success at first: of those who participated, only half as many returned to jail as in the non-psilocybin group. The study proved controversial, however. Many critics argued that there was no adequate control group. The patient not only received psilocybin, but therapy as well, so it was feasible that it was the therapy that caused the lower remission rates (for an in-depth follow-up study see this document).

The other noteable experiment was the Good Friday experiment, which took place in Boston University’s Marsh chapel in 1962. Leary’s team was interested in whether psilocybin could reliable induce a mystical experience. Religiously-inclined volunteers were randomly assigned to either receive an active placebo or psilocybin. The answer was a resounding yes. Almost all participants reported profound mystical experiences. Among the participants was Huston Smith, who later became one of the world’s leading religious scholars, and who described his encounter with psilocybin as “the most powerful cosmic homecoming I have ever experienced” (see Smith H. (2000). Cleansing the Doors of Perception; for more info on the experiment see this follow-up study).

During this period, Leary had yet to understand the importance of set and setting. He recognised that the experience was largely determined by the participants’ personality, their surroundings, and their preconceptions about what they were about to experience. Within the grey concrete walls of the prison, many more patients had difficult experiences, compared to people in a cozy domestic setting. Leary was well aware from personal experience that psychedelics can lead to difficult experiences, but he recognised that the risks could be minimised by careful preparation.

Psychology at that time was dominated by the ideas of Freud, who sought to explain most of the human psyche in terms of childhood impressions. Leary considered that intense psychedelic experiences involved essentially the same kind of imprinting, and was therefore convinced that guided psychedelic sessions could rewire the brain for the better.

Leary and his team felt that this was not an ordinary research project. They knew that eventually mind expansion would go mainstream, with major social implications. How were Western, materialist societies going to process the psychedelic experience, when the rational mind has no chance of doing so? What would materialists say to the idea that the mind expands faster than the early Universe immediately after the Big Bang? These were questions which Leary frequently discussed with the author Aldous Huxley. Huxley convinced Leary that first of all, the leaders of American culture should be introduced to psychedelics, and they would then help to prepare society for what was to come. As a part of this plan, many leading intellectuals of the era were invited to psilocybin ceremonies in Leary’s house. The guest list included Allen Ginsberg, Arthur Koestler, and Jack Kerouac.

From left to right: Gingsberg, Leary and Metzner

This period was the calm before the storm in Leary’s life; dark clouds were starting to gather over his psychedelic agenda. The main reason was that his Harvard colleagues had started to question Leary’s research. The volunteers’ reports of hyperdimensional realities and encounters with spiritual beings made the project look suspicious. Furthermore Leary’s claims about the infinite healing potential of psychedelic experiences simply sounded too good to be true.

Importantly, none of Leary’s research connected to any other branch of psychological science, and the whole project had a cult-like vibe, rather than that of a serious scientific project. To make the situation worse, Leary obviously looked down on his non-tripping colleagues: how could one hope to understand the mind, if one was unwilling to explore it?!

In March 1962, about two years after the start of the project, the Department of Psychology instituted an internal inquiry into the project’s scientific value and the safety measures in place. Leary emphasised that out of 300-plus participants, only a handful had had negative experiences, while about 75% thought it the most spiritual experience of his or her life. Regardless whether psilocybin caused anxiety or euphoria, the drug’s potential to cause extreme emotional states made it an easy target.

The story of the “drug professor” quickly spread through the media, and public opinion turned against Leary’s activities. The idea of chemical enlightenment was just too extreme for a Christian nation raised on tobacco and alcohol. After some disputes, Harvard formally fired him, but he was untroubled by the fact at this point. He had much bigger goals than a successful academic career: he wanted to elevate humanity to its next, psychedelic era.

After leaving academia, Leary moved to Zihuatanejo, Mexico, to found the world’s first psychedelic training centre. The idea was to have a kind of Hotel Nirvana, where people could come and go as they wished, while learning about the responsible use of psychedelic drugs. The goal was to train “brain guides”, a 21st century cross between a psychologist and a traditional shaman, who could help others to have a safe journeys across hyperspace. In their free time, the participants shared their psychedelic experiences and listened to talks on topics ranging from Zen Buddhism to quantum physics. The goal was to create a psychedelic culture that maximised spiritual potential, while minimising risk factors.

The project began well – perhaps too well. As rumours spread about the psychedelic camp, more and more young people showed up looking for a more meaningful life than what was offered by materialist society. As the number of hippies increased, clashes with the locals became inevitable. After the build of some tension, in July 1963, Leary and his gang were forced to leave Mexico. Without any clear better alternative, Leary returned to America.

At this point the main issue for Leary was that he had completely run out of money. Luckily, an old friend, Peggy Hitchcock, offered to support him. Peggy and her brothers were sympathetic to Leary’s ideas, and having been born into a family of extraordinary wealth, could afford to help the venerable professor. Peggy offered the famous Millbrook estate for Leary to use, and also financially supported him over the next few years, during which time the estate, just 130 km from New York, became the heart and soul of the psychedelic movement.

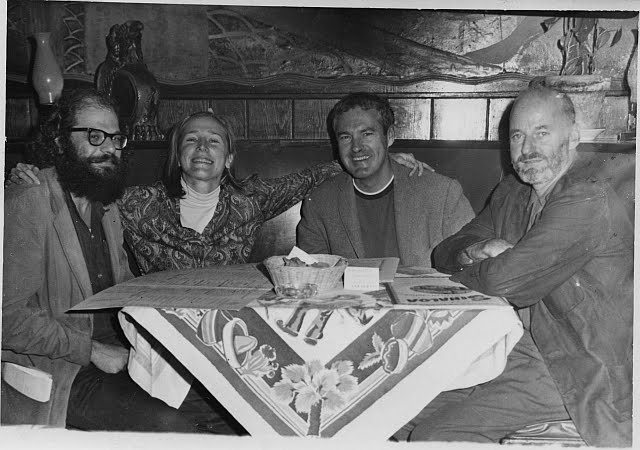

Allen Ginsberg, Peggy Hitchcock, Timothy Leary and Lawrence Ferlinghetti planning the next steps of the psychedlic revolution (San Fransisco 1963)

Leary and his closest companions were permanently resident at Millbrook, but many others came and went. There was always a room available in the sixty-four-room mansion. Amongst the constantly flowing people and ideas, the frequent use of LSD was the only stable factor. It’s worth noting that in the sixties, not only did acid kick in, but contraceptives too, offering much greater sexual freedom than ever before. As a consequence, Millbrook was also a semi-open sexual community. Leary thought of Millbrook as an experiment where the aim was to develop a lifestyle for the 21st century.

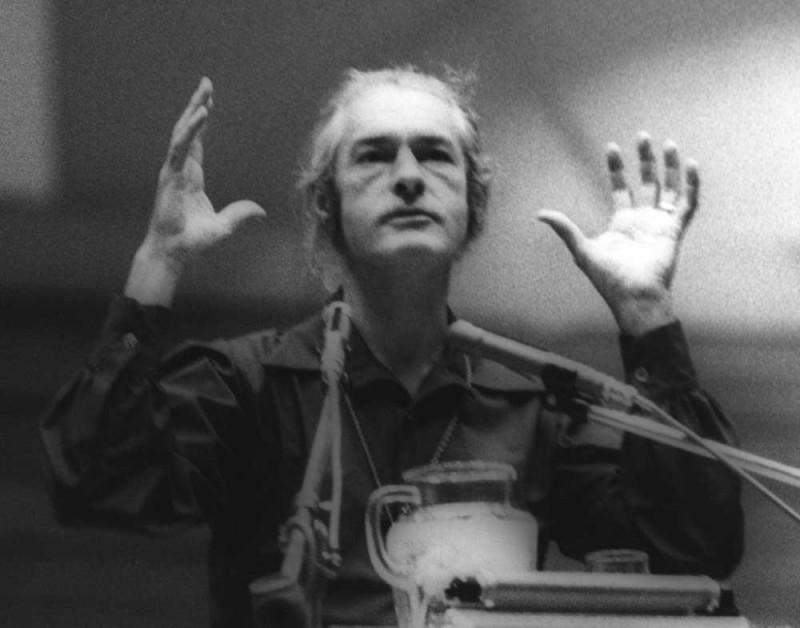

Leary in front of the Millbrook castle

During this time Leary was already a living legend, the messiah of humanity’s new psychedelic era. He talked and wrote a lot about how the use of psychedelics can activate dormant neural circuits, and hence offer a new perspective on problems. The newly-active neural circuits would activate a higher level of consciousness, allowing these substances to be the focal point of humanity’s next evolutionary step.

In the eye of the public, he was a unique mix of rock star and religious leader. The media was attracted to his controversial personality and Leary always tried to say something memorable in every interview. He was regarded by everyone as a charming, charismatic personality, although many thought him to be extremely egocentric, wanting above all else to be the centre of attention. It was during the Millbrook years that his famous Turn on, tune in, drop out! slogan became well-known across every college campus in the USA.

The happy Millbrook years came to end in 1965. At this time, the police were regularly visiting the estate and on top of this, a personal conflict between Leary and Alpert had unfolded. Leary thought that many of Alpert’s friend around Millbrook used LSD too liberally, to have fun, while he thought it should be used only for the purposes of spiritual evolution (although according to many accounts Leary also often used acid without much purpose). With his new girlfriend, Rosemary, Leary left for San Francisco, which had by this time become the hippy capital of the States.

In the mid-sixties, psychedelics (with the exception of marijuana) were still legal. Acid symbolised the rejection of society’s materialistic values, and had became a very popular experimental tool among American youth. Leary encouraged people to try LSD, but in all fairness he also emphasised that it is not for everyone, and certainly not for every occasion. He wanted to develop a system where the use of psychedelics would be conditional on obtaining a personal licence, after participating in a training course. At a Congressional hearing in 1966, Leary argued that, just as it is more complicated to fly a plane then to drive a car, more preparation is needed for someone to take LSD than to smoke marijuana. The idea was that people should be gradually introduced to more and more intense experiences. Leary’s efforts to make LSD a licensed and regulated spiritual tool were unsuccessful, and on 6th October 1966, the drug became illegal to possess and to use in the USA.

During the winter of 1965, Leary was heading to Mexico for a holiday. At the border, he was caught him with a small quantity of marijuana, resulting in a criminal trial against him. At this point, he was already public enemy Number One. in the eyes of conservative Christian America; President Nixon once famously called him “the most dangerous man in America”.

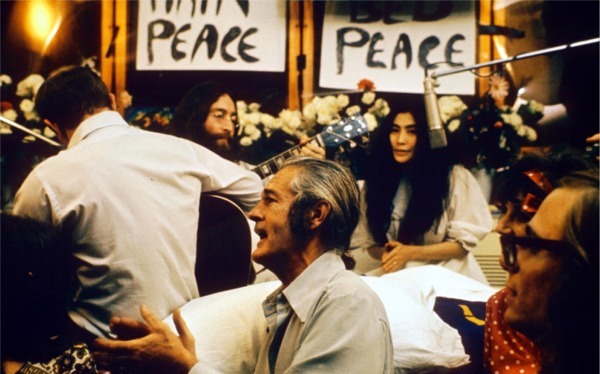

In 1969, Leary surprised everyone, when he announced his candidacy for Governor of California. He had the support of the whole counterculture movement. John Lennon and Yoko Ono invited him to Montreal, to participate in the famous sit-in which resulted in the legendary Give Peace A Chance song (if you look carefully Leary appears in the clip). Jimi Hendrix also openly endorsed him. The official song of the campaign was Lennon’s Come Together, written for this occasion. Leary’s political program was ideological at best: a unique mixture of communism and spiritual traditions. His program was rather like a wishlist, and he barely talked about how he would actually lead California to the promised land.

Leary with John Lennon and Yoko Ono

His conservative opponent was Ronald Reagan, the future President. Reagan vs Leary: the silent majority versus rebellious youth – it looked like a race for the ages. In the end Leary was not able to stand, as he was convicted of possessing marijuana and in 1970, was sentenced to twenty years in jail. Leary was 49 at the time, so this was effectively a life sentence for him. Luckily for him, he was sent to a low-security prison, and from the first day, his mind was set on escape. He observed the daily life of the prison for a few months, and on September 12, escaped the prison by climbing out via a telephone wire.

He knew he couldn’t remain in the states for long, so, using a fake passport, left for Europe. After a few inconvenient months in Algeria, he ended up in Switzerland. He applied for political asylum, and was allowed to stay while the legal process ran its course. A few months later, the Swiss state acknowledged that it was inhumane to imprison someone for twenty years for a small amount of marijuana, but he was not granted permanent residence, as the country wanted to avoid diplomatic conflict. He was given a year to leave the country. At this point, Leary’s girlfriend had left him and he was struggling with depression. He later said that this was the darkest time of his life. He even started shooting up with Keith Richards, the legendary guitar player of Rolling Stones, despite having earlier looked down on the use of opiates.

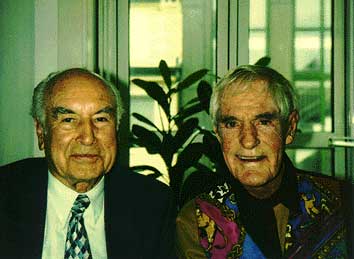

During his stay in Switzerland, Leary had a few meetings with Dr Albert Hofmann, the chemist who discovered LSD. The two men had a very respectful relationship: Hofmann had discovered the most potent mind-bending drug, and Leary had spread the news throughout the world . They were the father and the high priest of acid. They spent many afternoons together, walking in the Alps, and Albert even showed Leary the route of his famous bicycle trip. They had endless chats about the future of psychedelics and the role of mind expansion in science and evolution.

Leary and Albert Hofmann: the prophet and the creator of LSD

In October 1972, his stay in Switzerland came to an end, and Leary headed East. He went to Afghanistan, but his plane had scarcely touched down when he was captured by US government officials, and he was forced back to the USA. He was convicted again in 1973 for his prison escape. This time he was sentenced to the famous Folsom Prison, where his next door cell neighbour, for a while, was the mass murderer, Charles Manson.

Leary was constantly making deals with the authorities to reduce his sentence and to upgrade his cell. As a consequence, he was moved almost monthly, and over the years, spent time in 41 (!) different prisons. It is likely that he was bartering information about his sources of LSD and marijuana, but it is uncertain exactly what he shared. He must have provided some valuable information, however, as his thirty-year sentence was reduced to a mere three years, whereupon he was free again.

After Leary was released from jail, he never returned to his old self. Many thought that the almost weekly consumption of LSD over two decades had finally caught up with him, while others conjectured that prison had made him dysfunctional. He found himself in a world where he did not have centre stage anymore. The hippies of the sixties had been assimilated into mainstream society, and had got themselves a job on Wall Street. Leary still wanted to be the messiah of the new psychedelic age, but he had no followers anymore.

In his final years, Leary became interested in futurology. His favourite topics revelved around the S.M.I.I.L.E. acronym: space travel, the expansion of intelligence, and the extension of life. Along with these new topics, he remained active in popularising psychedelics. In the early nineties, he became a huge fan of the internet, predicting that it would be the next big thing. He was probably the first ‘drug blogger’ of the world, updating the world on a daily basis about his drug consumption and experiences.

In 1995, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He had some half-baked plans about taking a huge dose of acid for the last time and having his body frozen, so that he could be resurrected when the necessary technology was available. He passed away on 31st May, 1996 at his home in California. Neither his last trip, nor freezing his body became reality, but Leary was able to play one posthumous joke on humanity: a company specialising in space burials took his ashes up into space. He remains still orbiting somewhere around the earth. Even if the psychedelic revolution did not fulfill its potential, he still managed to get into space in the end.

Bibliography:

Timothy Leary: Flashbacks. Tarcher/Putnam,US; 2nd Revised edition edition (1993)

Timothy Leary: Turn on, tune in, drop out! Ronin Publishing; 6th edition (1999)

Timothy Leary: Your brain is God Forgotten Books (2012)

Don Lattin: The Harvard Psychedelic Club HarperOne reprint edition (2011)

Martin A. Lee: Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD Atlantic Monthly Press; Rev. Evergreen edition (2000)