In this month’s Dose of Science, rather than focusing on a specific academic paper, we present an interview with Mendel Kaelen, a neuroscience researcher at Imperial College London, working in collaboration with Professor David Nutt and Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris. In this piece, we get an unprecedented window into the scientific conceptualization behind one of the world’s only active human neuroimaging laboratories investigating the effects of LSD in combination with music.

DoS: Hi Mendel, thanks for taking the time to speak with us! Can you describe how your background led you to the current research path you’re on now?

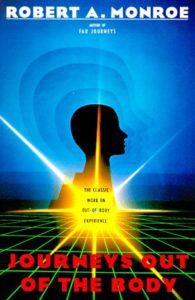

MK: I started as a Biology student, I wanted to become a Marine Biologist actually. And in that period I read Journeys Out of the Body by Robert Monroe, who wrote about having spontaneous out-of-body experiences, which I found really fascinating – both the phenomena itself, but also the questions about consciousness that arose from that. This was in 2004, and at the time I didn’t have much of a clue about what psychedelic drugs were, and Monroe was really the primary motivation for me to change majors and study neuroscience.

Mendel Kaelen

DoS: How did you discover psychedelics then?

MK: Because of my fascination with the altered states of consciousness described in Monroe’s book, I read articles about ketamine’s ability to induce similar states, and about ayahuasca and other psychedelics used in traditional ceremonies. That basically triggered a lot of interest – I realized that these compounds could be used to study their effects on consciousness within an experimental setting, by facilitating experiences that aren’t normally easily accessible or reliably evoked in people.

DoS: And then, suddenly…you’re conducting human psychedelic research?!

MK: (Laughs) No, not exactly. Though I had transferred majors from marine biology to neuroscience, my university professors at the time were not all equally supportive of this interest in psychedelics, but fortunately I found some good mentors at the university too. I became more interested in the clinical applications of these drugs, and one of them encouraged me to write essays, which I did for the use of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, and MDMA for treatment of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). I also got involved in organizing and attending conferences through the OPEN Foundation in Holland, but by the end of my Master’s I was really looking to do a long-term research project leading to a PhD position.

DoS: So like every other aspiring psychedelic researcher, you spent lots of time emailing people actively conducting research?

MK: Yes, I basically did virtually everything I could think of trying to network in the psychedelic community, but initially got very little hopeful responses. But in 2010 I met Robin Carhart-Harris at a conference in London called Breaking Convention, and after staying in touch he invited me to do an internship in his lab.

DoS: Sounds like quite the synchronicity! What was your early experience like working with the Imperial team?

MK: Indeed, I was quite lucky! During my six-month internship they published their first fMRI study using psilocybin in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (see Carhart-Harris et al., 2012), and they also received the first government grant to fund a depression trial using psilocybin. Additionally, Amanda Feilding from the Beckley Foundation worked to fund and collaborate on a human neuroimaging study with LSD, and I just happened to be there when they were looking for someone to help coordinate the study, and they asked if I wanted to make that my PhD project (see Carhart-Harris et al., 2016).

DoS: And you politely declined?

MK: (Laughs) Of course not! As you can imagine it was virtually impossible to say no to that. Although it took a year to really start the study, during that time we were having conversations about interesting research questions to explore, and that’s when the topic of music appeared. I have a background as a musician, and later while I was studying neuroscience at the University of Groningen, in Holland, I also worked as a sound artist doing installations and theater compositions, and I released a few albums as well. At some point, at the end of my Bachelor degree, I was seriously doubting whether I wanted to continue focusing on my art, sound art in particular, but I eventually decided to focus my efforts on researching psychedelic therapy. The opportunity at Imperial brought those interests together again through a combination with neuroscience and psychedelics.

Mendel performing

This was triggered when I was looking at a photograph of the Johns Hopkins team’s doing a session with psilocybin, and another photograph of an MDMA-assisted psychotherapy session with a PTSD patient, which showed the individuals laying down, eyes closed, listening to music through headphones. I had this realization that an important research focus for me was to begin working on understanding the therapeutic mechanism of music and psychedelics combined, and I was also tasked with developing the playlist for the psilocybin-depression trial (see Carhart-Harris et al., 2016).

DoS: What kinds of things were you exploring during that time?

MK: The research had slowly been coming out of the experimental blackout in only the past few decades, so scientists and therapists were – and continue to be – extremely thoughtful with their work, taking baby steps , with respect to the model that was developed during the intense period of research in the 1950s and 60s. Picking up where we left, so to speak. Despite the fact that from a scientific standpoint a lot of those studies were not well controlled – some even lacked a placebo group –, rather than throwing the baby out with the bathwater, there’s clearly knowledge that was gained from a therapeutic point of view.

That model currently remains considered by many as the best and safest way to structure the therapy – use of music during the psychedelic session, and a strong emphasis on creating a good interpersonal grounding between the therapist(s) and the patient before, during and after the session. This whole three phase process is considered to be very important for the psychedelic experience and the therapeutic response, and the scientific knowledge about this becomes more and more important. Because we’re now conducting research on increasingly larger scales, and there are some really basic, fundamental questions that need to be answered with modern scientific rigor. Questions like Why is the music necessary? What does preparation entail? What does integration entail?

DoS: Most of the current trials are heavily focused on clinical outcomes, which is obviously necessary in developing new treatments, but with the music being such a crucial aspect of the psychedelic session, it sounds like your focus was an incredibly important and overlooked area of study. How did you approach this challenge?

MK: For the depression trial that we ran a year ago I wanted to design a playlist that was specifically tailored for treating depression, as well as one that includes contemporary composers. A big problem I faced was that there’s not a lot of established scientific knowledge available in the literature on the use of music in psychedelic therapy. There is one important paper by Helen Bonny ,who out of her work as a music therapist, developed a well-known music-therapy method called The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music. Bonny and Pahnke describe in this paper how to structure music for therapeutic sessions with LSD alongside the different phases within the experience. This is however still largely theoretical. Also, though she developed a beautiful playlist that was used in psychedelic sessions at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, it contains primarily classical compositions, many of which are now very familiar pieces of music to many. An example is Samual’s Barber’s Adagio for Strings: An impressive work of art, yet clouded by so many associations, due use in movies, advertisements, and so on – which I think should be avoided. I also felt it was important to aim to acknowledge the personal music preferences of the participants for our psilocybin depression trial, as this is normally a determinant for how emotionally involved the listener can be with the music. The task to build a standardized playlist (every patient needing to listen to the same playlist) of course creates a complication for this, but as a solution I ended up building a variation into the playlist, including classical, neo-classical, ambient, jazz, and ethnic music.

Dr. Helen Bonny

Regarding the selection of the specific songs, though I combined some of the previous knowledge, I relied largely on my own intuition as a musician to bring the total playlist together. I tried to bypass my own music preferences, which is obviously very difficult. I asked myself for every single song, do I think this song works for me, or do I think it works because there may be something intrinsic within this song, which will reliably evoke an emotional response in most individuals who listen to it?

DoS: No offense, but that sounds like a very “unscientific” approach.

MK: Yes. The music playlist design has been primarily driven by artistic and psychotherapeutic intuition. There is at this stage simply no science to inform playlist design for psychedelic therapy, but this is a part of my current research focus. But this is not so deviant as it may sound to you. A lot of well-regarded psychotherapists shaping the field right now don’t necessarily have science that backs up the details in their approach. More often it is based on intuition and experience, which informs them what words to say, when to say it, and likewise what music to play, and when to play it. It does illustrates the importance of developing empirical standards for psychedelic therapies, to not end up like hundreds of other models of psychotherapy out there, many of which don’t have much scientific grounding beneath them. Which is a valid criticism for the field of psychotherapy and the field of mental health care as a whole. But it may also invite to ask a larger question, and that is what is the role of psychotherapeutic intuition in psychedelic therapy? Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy may really be the best we have at the moment in terms of empirical evidence, yet there’s certainly clear weaknesses in that approach.

For now, I reconcile these issues when it comes to music selection, to simply work with the knowledge present at this stage, on how perform sessions safe and effectively. And to not make too strong scientific claims, and rather, focus on doing the needed research. Studying that is a big challenge but also an exciting one. It’s a six-hour playlist, which makes it very complex and involves a lot of variables. There’s variance within the music itself, the different genres and acoustic features . Then there’s the individual’s subjective response which varies throughout the session along with the drug effect, and other non-drug variables, such as the personality, mindset and of course the interaction with the therapist. This is a big reason why many of the researchers conducting clinical trials with psychedelics want the playlist to be the same for each patient, since you should aim to control for all variables as much as possible within scientific experiments.

But there’s a problem with that too, because by controlling for the music, the design then doesn’t control for the individual’s therapeutic experience. You may then have people who have a strong drug-response, with strong therapeutic opportunities, but who end up not responding well to the chosen music, not being sufficiently therapeutically engaged with it. Or, the music may be totally out of sync with their experience, which is very dynamic. It is important to remind us that the same control doesn’t apply to the therapist’s interactions, since they would then have to behave exactly the same way for each subject, which obviously doesn’t happen.

DoS: There’s certainly a natural precedent for that in human history, specifically in ceremonial contexts, which of course combined psychoactive plants with the use of sound.

MK: When I first started getting interested in psychedelic drugs, one of the things that fascinated me was that these compounds are used across many different cultures around the world, and to my knowledge, music is always present in these ceremonies. Even in religious ceremonies that don’t involve the use of drugs, very often music – or sound at least – is still a central element, like in Christian, Musilim, Buddhist and Christian traditions, for example, music is often an important part of the ceremonies. Music and psychedelics both have a very old history, with strong ties to shamanism and spirituality. One of the oldest instruments to be reliably identified is a highly sophisticated ivory bone flute found in Germany which is estimated to be about 35,000 years old!

Image of the ancient bone flute

DoS: Exactly! So an anthropological perspective perhaps fills that problematic gap in the scientific literature of the more recent history of psychedelic psychotherapy research.

MK: So this is where we may find solution to the argument earlier about controlling music versus therapist interaction. If you harmonize both of these views – the therapist can adapt the music as long as all the changes are documented. Simply by tracking the different musical genres, artists, and even different acoustic features used, to ensure a balance over the different conditions, the design has the best of both worlds.

DoS: But ceremonial contexts usually involve live instrumentation, can you see a future where that is part of psychedelic trials?

MK: One advantage of live music may be that, if the music therapist (or a non-therapist musician) is good and intuitive, the music can be adapted in the moment, to fit the individual’s needs. From an experimental standpoint, this would definitely complicate things because it brings in more dynamics, including personal dynamics, that may decrease control over the therapeutic process and outcomes. However, there are many points to be made about how the presence of a trained music therapist during a psychedelic session may strengthen the overall therapeutic work, such as the therapist then having good knowledge, skills and intuition on music-use. Also, the attention the patient then receives, which would involve tremendous personal acknowledgement and intimacy, songs being played for them, they’ve likely never received before in any kind of mental healthcare setting. But I think it’s easy to romanticize live acoustic instrumentation. There’s a fascinating world of sound art and contemporary composers doing very new things with music, that are not possible with acoustic music. In developing psychedelic therapy, it is important to incorporate wisdoms of western traditions and the opportunities that contemporary artistic and technological advantages bring.

DoS: Can you speak more directly about the therapeutic effects of music studied in your work?

MK: We did a qualitative analysis of interviews with the patients in the depression trial about their subjective experience of the music, and one finding was that patients’ describe the music as either being resonant (in tune) or dissonant (out of tune) with their own inner feeling states. We found that the degree of resonance patients reported correlated with therapeutic outcomes and the occurrence of peak experiences and insightfulness. The more patients described a sense of music being in sync with their own feeling states, the stronger their reductions in depression were. These findings are preliminary since there wasn’t a placebo control but it helps contribute to establishing hypotheses we can explore further. For example, as to whether this dissonance versus resonance spectrum is something that could be optimized when there’s an adaptive approach with the music.

DoS: And what about the changes in the brain that are going on? The majority of the Imperial team’s focus of course has been on the neural correlates of the psychedelic experience, but so far much of what you’ve described is qualitative.

MK: First of all, the human mind makes music from sound – it’s our mind that makes connections between the different features in the sound. One study that we’ve been working on recently is looking at all the different acoustic features in music, and see which networks are involved in the processing each of the features. We decomposed pieces of music into features such as brightness, frequency, tempo, tonality, changes in major and minor key, and so on. Then we put all of these dynamic features into one model, and compared how they’re processed differently in the LSD condition versus the placebo condition.

One of the biggest differences in brain functioning we’ve found under LSD is the way the brain processes the timbre of the music. Timbre, or tone colour, is the acoustic quality that the brain uses to categorize objects in the outside world, like differentiating between the sound of the wind through the trees versus the sound of somebody whispering, or differentiating different voices. Timbre is also thought to function as an interface between sound and the emotions attributed to the sound. Under LSD we found an increased responsiveness to that feature, which was localized into brain regions involved in interpretation of meaning and emotion, language processing, including Broca’s area, parts of the auditory cortex, and the insula.

In one of my first papers we looked at particular music-evoked emotions, and we showed an increase under LSD in emotions like wonder and transcendence (see Kaelen et al., 2015). In this new study we replicated this, and we also found these emotions to be correlated with functional changes in brain networks processing timbre under LSD. Now we’re also using a different neuroimaging modality, Magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures brain activity in a much smaller temporal resolution, so we can look at all the different frequency bands of brain activity or neuronal oscillations, which we can then use to measure associations with different features in the music and how the brain processes these features under LSD. I discussed some work here that is in submission or part of my PhD thesis, but that both will hopefully see the daylight for your readers from not too long from now.

DoS: Thank you very much for your taking the time to speak with us, we’re very excited about the work you’re doing and eager to learn more from your findings.

MK: Absolutely, I’m honored to have been featured in your first interview! Your readers might be interested in an online study we just launched. One part of this looks more broadly into “setting” variables. While there’s no control group or placebo condition, and these experiences are happening outside of the laboratory setting, such a naturalistic study brings also new opportunities.

DoS: Fantastic! Here’s the “Psychedelic Survey” link for those interested in participating.

Kevin Franciotti