The legal regulation of drugs is more effective and just than prohibition. But does it really fix most problems? Not without social justice. (This article is available in Spanish, Portuguese and Italian)

“Stop the Drug War and Legalise Drugs!” – More and more people identify with this message. I am a strong supporter of drug policy reform myself. I believe that it is immoral to punish someone for using drugs. I am convinced that a regulated legal market, adjusted to specific types of drugs and risky behaviours, is much more beneficial for humankind than a global black market.

I don’t like prohibition because it proposes an over-simplistic solution to a complex problem. However, I feel that arguments based on the assumption that legalising drugs will fix most problems are just as over-simplistic. Don’t get me wrong, several problems we experience in this field are directly connected to the war on drugs, including over-incarceration, infections, overdoses, and organised crime. The black market of drugs is like a beast which is fed and fattened by efforts to repress it. Legally regulating drugs, on the other hand, would starve the beast.

But simply legalising drugs will not kill all the beasts.

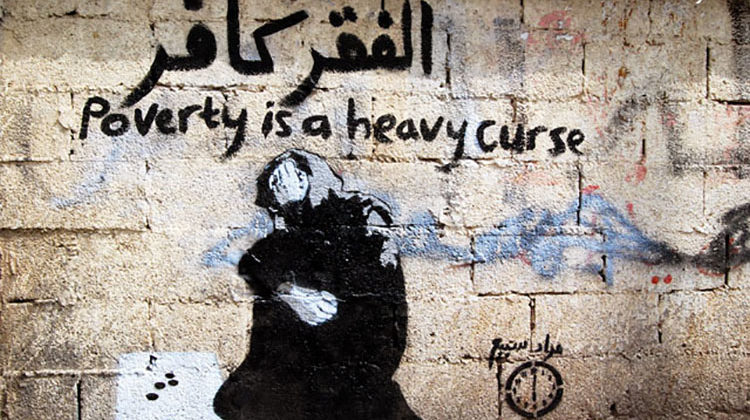

There are even bigger predators, often hiding in the shadows, lurking, looking for prey. Poverty, racism, domestic violence, homelessness, unemployment, bigotry, corruption, inequality, and so on. Without these beasts, repressive drug policies could never prevail in the first place. The war on drugs is an institutional tool for those with power and money to discipline and repress those with no power and money. Why? To gain more money and power.

It is not accidental that marginalised people who live in poverty suffer the most from drug-related harms – and from the war on drugs as well. These are the people who fill prisons but have no access to basic health care. They get infected with hepatitis C and HIV, die of overdose and AIDS, at much larger rates than well-integrated middle class drug users. In many countries they are imprisoned, tortured, killed and detained in boot camps. While rich people sniff cocaine, avoid prosecution, and access luxury rehab centres, poor people inject methamphetamine, smoke crack, and go to prison, especially if they are not white. The victims of Duterte’s death squads, Mexican drug cartels, or South-East Asian executions are all predominantly poor people.

Inequalities even manifest themselves in the drug market itself: crime lords, bankers, and corrupt politicians – most of them rich white people – benefit the most from the exploitation of poor farmers and consumers, on both sides of the illicit market.

The beasts of social inequality and racial discrimination nurtured drug prohibition and, unfortunately, they will also outlive it. When cannabis markets are legalised in the US, it is again rich white people who profit from cultivating and distributing the product. Poor communities, devastated by the war on drugs, stay marginalised and excluded.

The war on drugs is only a manifestation of a greater social injustice. Simply ending the war on drugs will not stop those underlying forces that fuelled it for many decades. Therefore we cannot reduce the drug policy reform movement to a legalisation movement, as its opponents often label it. This movement is about so much more than legalisation. We acknowledge and promote legal regulation – but we aren’t fighting for a small elite to profit from legal drugs. Our movement is first and foremost a movement for freedom and social justice. We are fighting for a drug policy that protects the weak from the powerful, safeguards the rights of consumers from profit-seeking companies, and gives back the self-esteem of people who are stigmatised.

Beyond legalisation, drug policy reform has to embrace efforts to end the exploitation of farmers in producer countries, invest in development programs, and make sure they have a fair share from legal drug profits. Drug policy reform must go hand in hand with interventions addressing institutional racism, sexism, and discrimination, not only in the criminal justice system but in the public health and social care systems. We have to stop residential and educational segregation, provide decent housing and jobs for drug users in poor neighbourhoods. We have to provide access to treatment and harm reduction programs, sensitive to age, gender and sexual orientation. We have to involve marginalised communities in the making of decisions about themselves, as well as mobilising them to enjoy the same rights as everybody else.

At the end of his life, Martin Luther King realised that simply abolishing legal segregation and adopting laws protecting civil rights would not end the oppression of black people. He worked tirelessly to expand the civil rights movement into a movement for economic justice, to eliminate poverty. Similarly, our drug policy reform movement does not end by making drugs legal. It is a necessary – but not sufficient – step to reforming drug policies and creating a social environment where the benefits and risks of drug use are equally distributed.

Peter Sarosi