Commissioner Viviane Reding says the solution to the growing problem of legal highs is making them illegal – but declines to discuss the unintended consequences

“Do you know what 'Spice' or 'meow meow' are? Things that sound innocently amusing can be deadly. These are the names of new psychoactive substances (NPS)s which mimic the effects of illegal narcotics such as ecstasy or cocaine. But make no mistake, those so-called legal highs could equally be called lethal highs, because although they are legal alternatives to illegal drugs, they are dangerous to health, and can be fatal.” These were the words with which Viviane Reding began her press conference.

In her introduction to the subject of regulating proposed new legal highs, the European Commissioner responsible for justice and home affairs announced that, “Today is the moment when we make dangerous legal highs illegal."

Reding told the media that the European Commission proposes to strengthen the European Union’s ability to respond to ‘legal highs’. Under rules proposed by the Commission, harmful psychoactive substances will be withdrawn quickly from the market, without jeopardising their various legitimate industrial and commercial uses. The proposals follow warnings about the scale of the problem, both from the EU's Drugs Agency (the EMCDDA) and Europol, and in a 2011 report which found that the EU’s current mechanism for tackling new psychoactive substances needed bolstering.

| Drugreporter asked EC Commissioner Viviane Reding – watch the video below from 8:55

Drugreporter Q: There is a broad consensus among experts that Europe's prohibitive drug regulation constitutes the main driver behind the boom in legal highs. Do you think it best to repeat the same mistakes we have made with traditional drugs, driving the legal high market underground and making it impossible to have in place the proper harm reduction measures for saving lives which evidence-based science shows to be best? EC Commissioner Viviane Reding A: This is the kind of discussion that I met 33 years ago, when I was in the national Parliament in Luxembourg. There were those on the prohibition side, and those who wanted to legalise everything. I do not intend to continue this discussion, 33 years later. |

|---|

"'Legal highs are a growing problem in Europe, and it is young people who are most at risk. With a borderless internal market, we need common EU rules to tackle this problem," said Reding, adding that a new substance appears on the market every week.

According to the EC, the number of new psychoactive substances detected in the EU has tripled between 2009 and 2012 (from 24 in 2009 to 73 in 2012). Since 1997, Member States have detected more than 300 such new substances.

The EC claims that this is a problem requiring a Europe-wide response. The new substances are increasingly available over the internet, and spreading rapidly between EU countries: 80% of new psychoactive substances are being detected in more than one EU country.

The EC claims that this is a problem requiring a Europe-wide response. The new substances are increasingly available over the internet, and spreading rapidly between EU countries: 80% of new psychoactive substances are being detected in more than one EU country.

The young generation is most at risk: a 2011 Eurobarometer on "Youth attitudes to drugs" shows that on average 5% of young people in the EU have used such substances at least once, with a peak of 16% in Ireland, and close to 10% in Poland, Latvia and the UK. These substances pose major risks to public health and to society as a whole, claims the European Commission. Statistics show that over 2 million Europeans have used NPSs despite the fact that most of these substances have never been properly tested for human use.

Speaking about real-life cases, Reding said that, “For instance, the substance known as 5-IT reportedly killed 24 people in four EU countries, in just five months, between April and August 2012. 4-MA, a substance which imitates amphetamine, was associated with 21 deaths in four EU countries in 2010-2012 alone”.

What regulatory changes are proposed?

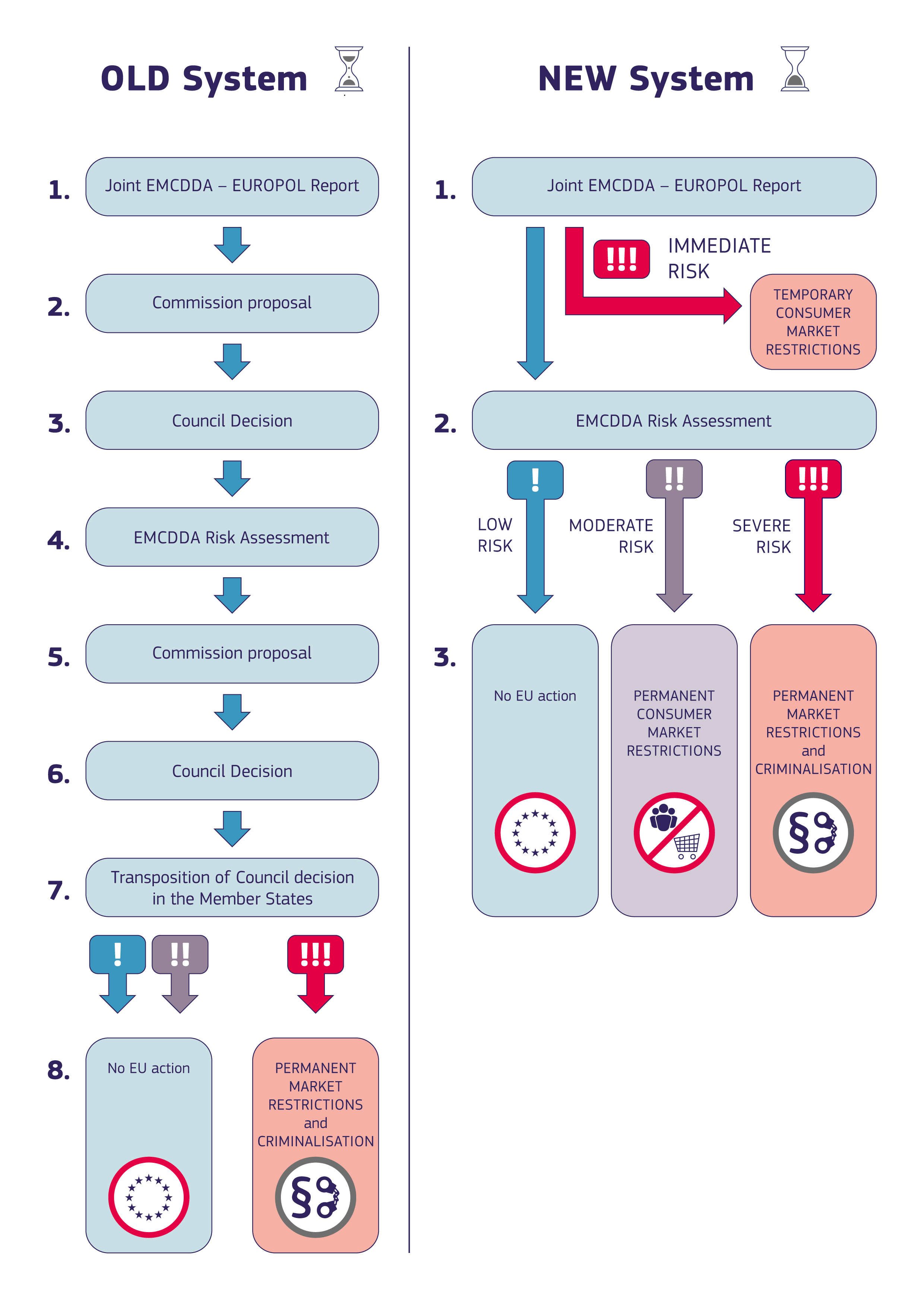

The current system, established In 2005, for detecting and banning these new drugs is no longer fit for purpose, the EC stated. A new, speedier system will therefore be introduced, if member states and the European Parliament agree.

It will consist of:

A quicker procedure: At present it takes a minimum of two years to ban a substance in the EU. In future, the Union will be able to act within just 10 months. In particularly serious cases, the procedure will be shorter still, as it will also be possible to withdraw substances immediately from the market, for a one-year period.

A more proportionate system: The new system will allow for a graduated approach, whereby substances posing a moderate risk will be subject to consumer market restrictions, and substances posing a high risk, to full market restrictions. Only the most harmful substances, posing severe risks to consumers' health, will be subject to criminal law, as in the case of illegal drugs. Under the current system, the Union's options are binary – either to take no action, or to impose full market restrictions and criminal sanctions. This lack of graduated options means that at present the Union takes no action in relation to some harmful substances. Under the new system, the Union will be able to tackle more cases and deal with them more proportionately, by tailoring its response to the risks involved and taking into account any legitimate commercial and industrial uses.

The Commission's proposals now need to be adopted by the European Parliament and by member states in the Council of the European Union, in order to become EU law.

Under the existing EU Council Decision, the Commission can propose to member states that new drugs should be subjected to criminal law. Under this mechanism, nine substances have been submitted to restrictive measures and criminal sanctions. Back in 2010, the Commission proposed and achieved an EU-wide ban on the stimulant known as mephedrone, and it did the same thing, in early 2013, in relation to the amphetamine-like drug 4-MA. In June 2013, the Commission also proposed banning the synthetic drug, '5-IT'.

An unnamed EC expert, addressing a question from Drugreporter, clarified that under the proposal, only the manufacture and sale of highly dangerous legal highs will fall under the penal code, as the European Commission is against punishing simple use or possession.

György Folk/Brussels