A case study by our guest author David Haddad on Methoxetamine, misinformed media and prohibition as a failed approach towards New Psychoactive Substances.

Naughty Plant Food. Bath Salts. Incense. 5-meo-DiPT. Mexxy. NBOMes. Charlie Sheen.

The list goes on.

New Psychoactive Substances, sometimes called Legal Highs or Research Chemicals, are a diverse class of drugs which includes stimulants, psychedelics, dissocciatives, cannabinoids, and opiates. NPS are categorised as “new” due to having a relatively short history of human consumption and only recently becoming available through headshops, online vendors, and even street dealers across the globe. They are sold as legal substitutes for already banned substances, as novel highs in their own right, and are sometimes used to cut black market drugs. One of the biggest concerns surrounding NPS is that due to their short history of use, some may pose unknown and serious health risks. It is already documented that some NPS do carry well-known and serious risks; although the purported health risks of others have been blown out wildly out of proportion.

We need to acknowledge that NPS provide the most robust examples of how prohibition has failed, by looking at the ways attempts to ban NPS have proven ineffective: such attempts have only resulted in a more diversified and innovative market, several steps ahead of law enforcement, and always ready to skirt the next round of legislation. Bans imposed on current NPS only lead to the introduction of a new wave of previously-unheard-of psychoactives with unknown safety profiles, which may cause more dangerous compounds to appear on the market. We need to consider that attachment to prohibition as a strategy for drug policy, in the long term, may actually be a disservice to public health, since drug users who wish to be compliant with the laws in their jurisdiction are encouraged to use ever more experimental drugs as NPS continue to be banned. We need to acknowledge attachment to prohibition as the elephant in the room. We need to open the floor for discussion in order to ask society and policy-makers for a re-evaluation of the issues underlying substance use and intoxication. We need to ask if government has the right to tell individuals they are not allowed to exercise freedom of thought by experiencing certain kinds of mental states. We need to ask: Isn’t cognitive liberty a human right?

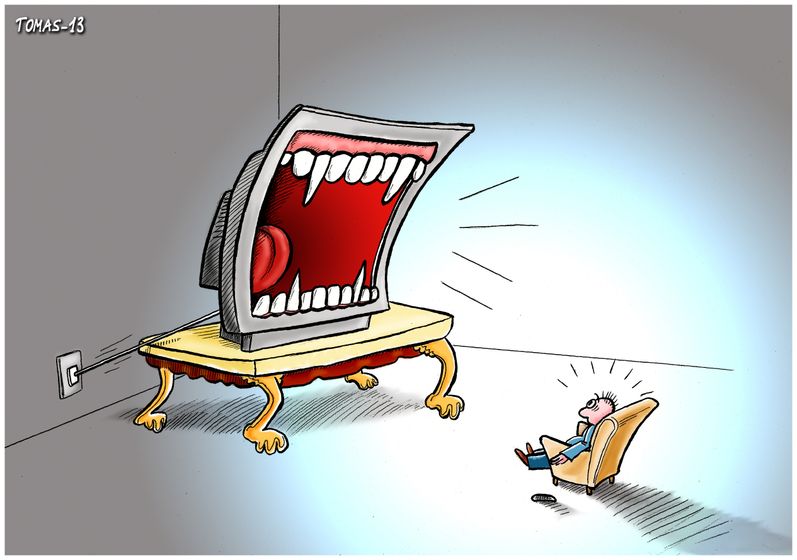

There is some excellent work being done by civil society, calling for education, risk management, and a move towards regulation. Yet, there are also significant communication gaps between voices calling for drug policy reform, and legislators – who want to reduce criminalisation of drug use and offer rehabilitation services, but still want to maintain prohibitionist policies. Resistance to evidence-based approaches as a path to regulation is often informed by a lack of political will, in part because NPS are viewed as presenting more severe risks and side-effects. This perception of the imminent danger posed by NPS is often fabricated through unsubstantiated news stories which sensationalise horrific freakouts, health problems, and deaths. While deaths and other problems associated with NPS do occur, in far too many cases, media reports have no factual basis. We also need to address the additional problem of legislative bodies and drug-monitoring organisations which are resistant to drug policy reform, either due to mission statements predicated on maintaining prohibition, or sometimes simply because they lack a framework to determine appropriate levels of risk in order to make recommendations for regulation. A more serious problem that also arises is when relevant data on the medical and therapeutic potential of NPS, or already banned substances, are ignored.

To provide one example in a plethora of failed attempts to stamp out the use of NPS, let’s examine the case of methoxetamine. In 2010, methoxetamine, a designer dissociative drug with hallucinogenic properties, became globally available through research chemical vendors online and through headshops across the UK. Although, in the beginning, methoxetamine was mostly a British phenomenon, by 2011 it had become a commercial success with increasing popularity in Europe and North America. In 2012, it was already garnering bad press in the UK; by March, British media reported two fatalities in Leicester, attributed to methoxetamine; and by the end of the month, the UK Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs pushed through emergency legislation banning methoxetamine and other structurally-related dissociatives which fit the definition of arylcylcohexylamines. As indicated in their report, “The ACMD are not aware of any confirmed deaths solely related to methoxetamine reported in Europe or elsewhere in the world.” By June 2012, the Leiciester coroner’s inquests were made public, clarifying that the media reports of overdoses which had driven the methoxetamine ban were in fact not attributed to methoxetamine, but to unrelated prescription medications. It is worrisome that these false media reports were able to push through public policy so quickly.

The UK scene, however, was unfazed by the category arylcylcohexylamine ban, and in 2013, several new dissociative drugs became available, compliant with the new law. Then, in June of 2014, the European Union followed the UK lead and moved to ban methoxetamine. Of note is that in the same month, the World Health Organisation published a report from an expert committee on drug dependence which detailed methoxetamine’s acute toxicity profile and addiction potential, and claimed there was no evidence of its therapeutic use. It seems WHO is unaware that in October 2012 an article published in the journal Medical Hypotheses had detailed methoxetamine’s therapeutic potential as a fast acting antidepressant. In May of 2014, the European Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction published a risk-assessment report on the substance which claimed twenty analytically confirmed deaths attributed to methoxetamine – although the ECMDDA report only actually lists one of these deaths as solely attributed to methoxetamine consumption, with notes indicating that the cause of death was respiratory failure. Both the ECMDDA and WHO reports on methoxetamine indicate European seizures of multiple kilograms. After hundreds of thousands of doses have been consumed by individuals across the world, one fatality doesn’t seem to pose a particular menace to public health. And while the UK and EU member states banned methoxetamine, illegal consumption continued up until October 2015, when China's Food and Drug Administration banned production of the drug. But by January 2016, several structurally-related dissociatives had already replaced methoxetamine, in order to circumvent the ban.

Methoxetamine’s story shows us a media environment largely unconcerned with accurate, fact-checked reporting, policy-makers all too eager to present a skewed interpretation of toxicity data as a means to favor a ban without first calling for further evidence or investigation, and an industry of New Psychoactive Substances capable of evolving at a moment’s notice. In order to move forward in drug policy reform, we need the media to do their job covering the complexities of NPS, instead of cultivating an uninformed public and exploiting their fears in order to legitimise dated policy stances which infringe on the right to freedom of thought. We also need more policy-makers and monitoring organisations to establish safety profile criteria for NPS, moving them beyond prohibition and into the realm of regulation. As activists, advocacy workers, and journalists of integrity, we need to take seriously our role as educators with the power to shape public opinion and reframe debate on drug policy reform to focus on critically exploring attitudes towards prohibition. It isn’t believable anymore to say that legislation of NPS has public health as its main interest, in a world where the chronic consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and Big Macs is loosely regulated despite their posing significant health risks. Given these other, legal, lifestyle choices, arguing for prohibition in the name of public health seems like a moot point. We need to talk about our values, and about the role of the government in regulating cognitive liberty. We need to emphasise harm reduction, and focus on evidence-based approaches.

David Haddad