The president of Turkey declared a war on drugs – but is it really what his country needs? Read our report from Istanbul!

The Turkish Green Crescent Society invited me to speak at their International Symposium on Drug Policy and Public Health in Istanbul. The conference was attended by more than a thousand participants from 50 countries – an excellent forum for the president of Turkey to address the international community with a long opening speech about drugs, terrorism and politics. Well, mostly about politics. The president lambasted European countries for applying double standards in their treatment of different terrorist groups – attacking ISIS, but supporting the Kurdish PKK just because the word “Islam” is missing from PKK’s name. He said that ISIS has nothing to do with Islam, but rather consists of militants who are drug addicts. He claims that the core problem is not religion, but materialism, and that drug addiction itself is the result of a lack of moral values. Religion, he contends, protects young people from the threat of drug addiction, and he therefore rejects the ruling of the European Court of Human Rights, which found that the Turkish government had violated the right to freedom of religion and consciousness by making religious education compulsory in schools. He urged parents to wage a war on drugs at home while the government will declare a war on drug traffickers, who are associated with terrorists.

Mr. Erdogan, the President of Turkey is speaking out for compulsory religious education to stop drug use

There are different models to explain the roots of addiction, but researchers agree that the moral model, (claiming that people become dependent on substance use or other behaviours because of their moral weakness), is outdated and false. There are so many social and psychological factors underlying problematic drug use: for example poverty, social exclusion, poor parenting, child abuse and neglect. These problems can be addressed by public health and social care systems with evidence-based, non-judgmental services. Spiritual experiences can empower people to improve their health and well-being, true; but institutionalised religion can also strengthen the stigma and discrimination which make young people more vulnerable to problematic drug use. There is no evidence to support the claim that compulsory religious education will lead to less drug problems among young people.

Responding to a sharp increase in drug supply and demand in the past couple of years, the Turkish government introduced harsher penalties against drug dealers in June this year. It is unlikely that harsher laws will stop the growth in drug use. The military approach to drugs, the so-called 'war on drugs', has been proven to be not only unwinable, but remarkably costly and harmful. Turkey itself criminalised more than 130,000 people for drug offences in 2012 alone – 100,000 more than in 2008. Most were young people who smoked cannabis. Despite criminalising more and more young people, the government did not manage to deter others from drug use.

While at the conference, I learned that the Turkish government had banned ESPAD (a survey monitoring drug use patterns among schoolchildren in most European countries) because the Ministry of Education claimed that the questionnaire might encourage young people to use drugs. I find it absurd that the same government which is criminalising tens of thousands of young people for smoking cannabis, says that it's worried about the harmful impact of a questionnaire on their mental health. Unlike criminalisation, a well-conducted research questionnaire has no proven negative impact on teens.

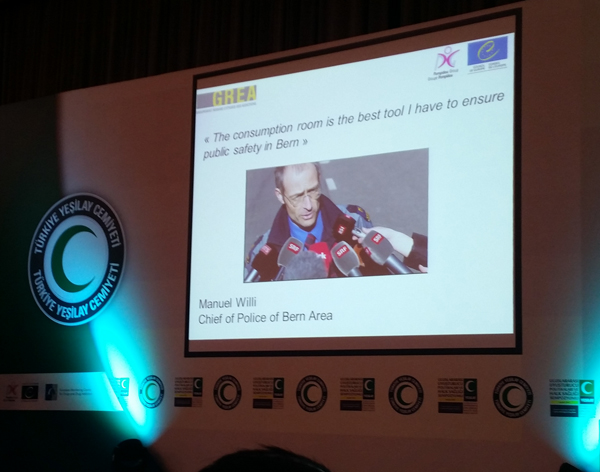

A presentation about drug consumption rooms in Switzerland

My presentation about global access to harm reduction and about advocacy to bridge the funding gap

The conference, organised by the Green Crescent Society, was an important milestone for Turkey to improve its public health response. For many participants, this event might be their first opportunity to learn about the prevention, treatment and harm-reduction programs which have proven to be effective in other countries of the world. Best practice was presented from countries such as the Czech Republic, Switzerland, the UK, and the Netherlands. It was equally important to present 'worst practice': what happens if governments do not spend enough on harm reduction programs, for example. My own presentation was about the funding crisis for harm reduction in Europe and its grave consequences, as well as advocacy efforts to bridge the funding gap.

A presentation about opiate substitution treatment – the first pilot program has opened recently in Istanbul. It's time to open the first needle exchange programs too!

It is very important for the Turkish government to realise that there is a difference between recreational and problematic drug use. Not all drug use is problematic, whether it is legal or illegal. A significant number of young people experiment with drug use in post-industrial societies, without becoming dependent or having significant health problems. This does not mean that we should not worry about the risks of drug use and do whatever we can to prevent harms – for example, by creating a safer environment and protective social norms. But a zero-tolerance approach that demonises drugs and drug users, accuses young people of moral weakness, exaggerates harms, and pursues the unattainable ideal of a drug-free society will not provide a real solution, but instead will inevitably become part of the problem.

Peter Sarosi