It’s common for governments to use ‘protecting the youth’ as a justification for punitive drug policies. The policies governments are propagating, however, are not evidence-based and show little knowledge of how young people use drugs. Read an intriguing report about youth activists who fight for drug policy reform written by our intern, Hannah Taylor!

“So we’re used as this prop for them to be able to justify these drug policies because it’s fearmongering. They’re being like, ‘Young people will die unless we do this.’ …but they don’t know what they’re talking about. They don’t have any evidence to back that up,” shared Róisín Downes, SSDP’s Global Program Coordinator.

Young people, however, do know what they’re talking about. Their voices and their experiences should be treated as valid within civil society and decision-making spheres. Students for Sensible Drug Policy and Youth RISE are two international organizations focused on engaging young people in harm reduction and drug policy reform. This mini-series focuses on 6 young activists who are working around the world to fight for drug policy reform and to protect human rights.

Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP)

SSDP has 5,000 members in over 30 countries, and is a network of primarily university-based chapters that work towards the shared goal of ending the war on drugs. Joining SSDP gives you access to the organization’s Peer-to-Peer education program, Just Say Know. It also grants you access to a worldwide network of people with on-the-ground experience, though they may be working in anything from cannabis policy reform to psychedelic-assisted therapy to low-threshold harm reduction. By joining the organization’s Facebook groups, you become aware of breaking articles, webinars and events, and access a wealth of knowledge from other members. If you are looking for a specific type of information or support, they do their best to connect you to someone or some resource within their network.

“I’ve learned so much since joining SSDP about how to stay safe while using drugs that I wouldn’t have otherwise known. That’s just from me educating myself so that I can then educate others…you get a much better understanding of how to stay safe and keep your friends safe,” shared Dasha Anderson, who currently leads SSDP United Kingdom.

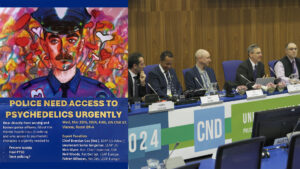

Concrete opportunities available to SSDPers are the opportunity to be trained in UN advocacy and to attend the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs, an annual international meeting on global drug policies held in Vienna each March. Another opportunity is to access scholarships for the biannual International Drug Policy Reform Conference, organized by the US-based Drug Policy Alliance. Members can network with high-level organizations including the International Drug Policy Consortium. Even if a member works only within their local chapter, they can develop valuable advocacy skills.

“I think it’s been great for confidence, like I’m so much more confident speaking to people now than I was before. It’s just a great way of building skills that you wouldn’t otherwise have: organizational skills, being able to secure funding for things,” said Dasha of her time as chapter leader.

SSDP is currently restructuring, and its Global Program will be establishing an office in Vienna next year. The vision is to make SSDP, which originated in the United States and has been dominated by U.S. American and Western ideas in the past, more global to reflect its membership. The idea is to put the power for decision making and organizational initiatives more in the hands of members. This will also mean creating more regionally-applicable resources and increasing access to global funds for on-the-ground initiatives.

“Our job is to facilitate the work, not dictate the work,” shared Róisín.

Youth RISE

Youth RISE is a decentralized organization which is made up mostly of people who are already involved in harm reduction work or organizations in their own country. That decentralization allows locally-informed and responsive actions, while feeding lessons from those efforts back into a global community. Additionally, Youth RISE members are in and of their communities, which is key for having a greater impact.

“Having that sort of insider knowledge and having such a deep level of trust of the community members and having such an understanding of what is necessary in each region…Like I’m never going to [fully] understand as the [Executive Director] of this organization, what is necessary in Peru or what is necessary in South Africa or what is necessary in Nepal,” said Ailish Brennan, Youth RISE’s Executive Director.

Youth RISE members and member organizations benefit not only from the wide-reaching network, but also from concrete activities, like workshops on capacity building and network development. Several new organizations stemming from Youth RISE have been established and now function on the local level. Youth RISE Nigeria, for example, has been an independent organization for over 5 years.

While Youth RISE is a decentralized organization, it benefits from strong communications structures, and activities that are organized to benefit the membership.

“Having best practices from these spaces are relevant to accelerate and to advance the advocacy that’s happening at the national level…It’s a constant learning space for me, challenging myself, embracing new perspectives and insights and also bringing to the country level, lessons,” shared Daniel Nii Ankrah, one of Youth RISE’s International Working Group Members from Ghana.

Another distinguishing characteristic of Youth RISE is its focus on Full Spectrum Harm Reduction, which it defines as incorporating all of the people who use drugs, all of the methods for using drugs, as well as the political, social, and environmental contexts for use.

“Black Lives Matter [is] a very good example to begin with. How a person’s skin color interacts with the world in general, but also with their drug use, and with their access to harm reduction services,” Ailish explained.

This becomes clear to Ailish in Berlin, where she lives, every time she enters a public park. The most visible, and therefore vulnerable, people selling drugs are people of color, primarily male refugees from sub-Saharan Africa. These people are excluded from safer ways of selling drugs, and more likely to be targeted by the police based on their skin color. With poor social welfare systems in place, they may not have a car or a flat from where they could more securely sell.

Other important considerations for full-spectrum harm reduction are if the services offered are gender spectrum-inclusive, as most are built with a male client in mind, and that the service can adapt to changes in the drug market and drug use patterns.

The truly global nature of the organization allows for collaboration across levels. Sometimes collaborations happen at the national, or regional levels, like West Africa or Asia or Europe. They make a plan for the year, and tend to keep that structure, but also tend to have some spontaneity to respond to pressing issues, as was the case with COVID-19.

When a Youth RISE member has an idea or proposal, there is a wealth of available experience to draw on to help refine it.

“I am able to consult…sex workers, consult drug user communities, consult other people who come from different backgrounds, and then maybe harmonize their perspectives and concerns and insights into concrete advocacy material that, together with a few of them, I can present on their behalf.” Daniel feels that Youth RISE has helped him to develop as an advocate in the broadest sense.

“I think that for a long time I have been more invested in national and regional-level advocacy work, but I think that Youth RISE is one of the platforms that made me see the essence in linking advocacy across levels, particularly to the global level,” he shared.

Getting into it

The first time Róisín noticed systematic inequalities was when she was around the age of 15 and she volunteered at a holiday home for elderly people from disadvantaged areas. She noticed something different about these elderly people; many of them wore gold necklaces with faces etched into them.

“I remember asking one of them once, what is that on your necklace? And it was their son. Their son had been murdered. The story, as she told it, was that he just walked outside the house and he was murdered. Just stabbed there and then. And this was a very common story amongst these elderly women.”

The area in Dublin that these women were from is called Ballymun, in inner-city Dublin. It’s known for having elevated crime levels and a concentration of drug use, especially heroin.

“I remember thinking, all of these people are from the same place, and all of these children are dying…we know this, the government knows this, this seems to be common knowledge. There’s nothing defining but where they’re from. That’s when I realized there was this systematic…issue of us just ignoring the lives of certain people from certain areas in Ireland.”

When Róisín first joined SSDP, she was a relatively passive member. However, she was inspired by their grassroots and adaptable approach to organizing. Her chapter’s goal was to get drug checking kits into the community, to enable drug users to find out the content and purity of substances they intend to use, so they can avoid accidental overdose and poisoning. They did so through Facebook and by travelling all over Dublin.

“They gave them out all over campus, at festivals… and all of this is quite undercover because reagent test kits in Ireland are not illegal but they aren’t legal either.”

After the news became aware of this and supported their efforts, the university went on to do the same. Eventually test kit distribution was absorbed by the Student Union.

As her studies in International Business developed, and she became more invested in economic policy and understanding inequalities around the world, Róisín eventually stepped up to become chapter leader of her university, Dublin City University. Her university happened to be in Ballymun.

“It all came back to Ballymun.”

Ailish, who is currently the Executive Director of Youth RISE, joined the organization two years ago as an International Working Group member. As a trans woman, she was aware of politics at a very early age.

“You’re kind of made very aware of that … my existence is somewhat political in a lot of places.”

Then, when Ailish was a teenager, Ireland had two referenda: one on marriage equality and another on reproductive rights. These were very widely discussed referenda, and the heightened rhetoric increased her interest in human rights and politics.

When she was in university, a medically-supervised safe injection site was proposed for Ireland and a license was granted for a site in Dublin, which led to public discussion around it, as well as around decriminalization. The timing coincided with changes in her own drug use.

“I started taking drugs, my friends started taking drugs. I realized that taking drugs and dancing to loud music is quite fun, so we started doing that a lot.”

However, the dangers associated with the criminalization of drug use became clearer and clearer, especially given a lack of harm reduction services. People were pushed to the margins of society without access to pragmatic, compassionate support to stay alive and healthy. Ailish brought this into her studies in politics, using every opportunity to talk about the war on drugs. After learning about SSDP, she went on to form the first chapter at her university.

Though Daniel had been involved in advocacy and working to serve vulnerable populations in Ghana for years, he became interested in drug policy when he worked on a research project focused on sexually transmitted infections. Along the way, he realized the widespread nature of drug use in the communities he studied. He went on to coordinate a research project between Ghana and Kenya which focused on policy interventions targeting young women who use drugs.

Even though drug policy reform isn’t his full-time job, the area is an intersectional one; it touches the vulnerable populations he works with and is a human rights issue. Furthermore, he feels that he is able to connect people from his work to other activists.

“In Ghana, the space is very very shrunk. So it’s important that some of us with other backgrounds that can open conversations are involved and also contribute experiences and invaluable time and resources to open up this space.”

Rory O’Brien, who is also a director of Sensible Minnesota, has been an SSDP chapter leader for over a year at her community college in Minnesota. Her first interest in harm reduction was not in relation to drugs, but rather sexual health education, in response to insufficient resources in U.S. public education. Her personal research into the war on drugs and its racist roots, combined with her family history of addiction, led her into drug harm reduction. When she started college, she decided to pursue an addiction counseling program, and a lecturer there encouraged her to join SSDP.

Dasha Anderson, who is about to finish her cognitive neuroscience master’s degree at Durham University, completed a module on Drugs, Crime, and Society and the overview of UK drug policy sparked her interest. From the angle of psychology and neuroscience, Dasha wanted to know how drugs work in the brain and how they affect the people she knows who use drugs. Dasha went on to become chapter leader of SSDP Durham and is currently working on establishing a nationwide network of UK SSDP chapters, of which there are currently 6.

Clement Bofa-Oppong came into the drugs field during the beginning of his time at the University of Ghana in 2016 when he was jumping between activities and groups, trying out anything that he found fulfilling.

“Anything that seeks to [positively] transform the society is stuff that I’m really in for,” he said. He started working with SSDP Ghana since its inception, pulling in friends and colleagues. This led to a critical reflection on drug-related issues in his own community.

Most of Clement’s childhood friends have developed problematic drug use, and lost opportunities for education and earning a decent livelihood because of it. Clement’s analysis of the context-specific dynamics surrounding drug use in Ghana show the importance of having organizational structures and supports dictated from the ground up.

“For us, unlike probably in Europe or America where most people want to try drugs because of the pleasure, because of the good feeling it will give you, here most people end up doing drugs because of broken homes, because of family issues, because of parental issues, because of economic hardship, because of poverty…they want to escape [their hardships].”

The penalties for drug use, sadly, resulted in already-rare opportunities becoming inaccessible. Prior to March 2020, you could be incarcerated for 5 to 10 years for simple possession of cannabis or other narcotic substances in Ghana.

In 2016, Clement went on to start the University of Ghana chapter of SSDP Ghana, with the desire to help those friends he had seen lose opportunities and freedom because of their drug use.

“This was time for me to also get back to [my community] and reach out to them, educate and support them in any possible way I can.”

Finding community

For young drug policy reformers, who can often feel isolated in their beliefs and fight for the human rights of People Who Use Drugs, finding a community in their work is powerful. Many remember the first time they were in a room of like-minded peers.

“At home I was like the only person who was really into this, you know? My friends agree with it, and they use drugs, but they’re not…as passionate and crazy about it…So I came back and I’m like so I’m not actually insane, there are other people who constantly think about this stuff,” Ailish recalled of her first international drug policy-related event.

That sense of community also lends motivation and strength to propel young people’s advocacy work forwards.

“I have always had the opinion that the drug war makes no sense, and that legalization, or at least decriminalization makes sense…When I started to realize that that wasn’t a super controversial opinion, or at least that there were other people who also held that opinion, I wanted to get more involved,” shared Dasha.

For minority groups within the drug policy advocacy space, finding others who have shared experiences can be a powerful source of strength and motivation.

“Through the broader SSDP global organization I’ve been able to connect with other black and brown people doing drug policy work, too. Some of the racism I guess I’ve faced in the addiction counseling program at school, and in the treatment industry, and even like in the harm reduction and drug policy communities… It’s been nice to connect with other people who have those experiences too,” shared Rory.

Being a part of a global movement can help each event and advocacy effort feel like a part of the bigger picture.

“It’s made me come to appreciate the fact that, you know, it’s not only in Africa or West Africa but also other areas across the world where there’s evidence of young people bringing positive results, positive change to their communities through drug policy advocacy,” Daniel said of how joining Youth RISE expanded his concept of drug policy advocacy.

Hannah Taylor

(The next part of the report is coming soon!)