Interview with Josch Steinmetz, the project manager of the largest safe consumption room in Frankfurt. The interview has been bupblished in the Addictologia Hungarica.

Interview with Josch Steinmetz, the project manager of the largest safe consumption room in Frankfurt. The interview has been bupblished in the Addictologia Hungarica.

Published as: István Gábor Takács: Konsumraum Nidda 49 – The Frankfurt Example of Harm Reduction II. Interview with Josch Steinmetz, the project manager of the largest safe consumption room in Frankfurt. Addictologia Hungarica, L’Harmattan Könyvkiadó és Interdiszciplináris Addiktológiai Fórum, Budapest, 2005. IV. évfolyam 4. szám (in Hungarian only)

Josch Steinmetz

photo: István Gábor Takács

Foreword

Now in many countries of the world, supervised consumption rooms (or safer injection rooms) are common harm reduction services. In these rooms people can use (mostly inject) certain drugs in a hygienic, low-stress and low-risk environment, while they are under constant supervision. The Hungarian Civil Liberties Union has been advocating harm reduction for more than ten years in Hungary. The aim of the present interview with Josch Steinmetz, the project manager of the largest safe consumption room in Frankfurt, is to provide experts with experience-based information on this issue. We discuss the concept of safe consumption rooms, the circumstances in which the idea of such rooms evolved, and the conditions necessary for their effectiveness. In the interview we also gain insight into the daily practice of a safe injection room.

The first official safe consumption room was opened in Switzerland, in 1986. New rooms followed in Germany and The Netherlands in the 90’s, Spain, Australia and Canada opened them in

The comprehensive study[1] of the EMCDDA on supervised consumption rooms concluded that these services are effective. They are able to reach those drug users who are struggling with health and social problems. They provide hygienic environment to drug use and at least for regular users of the rooms, they reduce the possibility of infections. They contribute to the reduction of risky behaviors and provide easier access to further help for hard to reach populations. They reduce overdose deaths by providing immediate aid. They promote the health status of people and they provide counseling and therapeutic assistance. With proper capacity and by cooperating with the police they reduce public use and nuisance. The studies have failed to confirm fears that supervised consumption rooms would facilitate drug use or they would motivate people starting using illicit drugs. The studies finally suggest that the chance that these rooms maintain drug use or they undermine therapeutic aims is very minimal.

By the Main river

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: What are the basic aims of an injection room?

Josch Steinmetz: There are three or four basic goals of supervised injection rooms. The first one is HIV and hepatitis prevention. The second one is to prevent and manage overdoses, to reduce drug related deaths. The next goal is to reduce the public use of drugs. The last goal is to get in contact with people who you do not reach any other way. It may be a first step into the drug help system, by means of counselling, making connection to detoxification or finding a place to sleep.

HCLU: Would you describe your institute please?

Josch Steinmetz: We are the second largest program of Integrative Drogenhilfe, which is one of the six drug care NGOs in Frankfurt. It mostly works in the field of harm reduction such as methadone treatment, injection rooms, working programs or shelters, including specialised shelters for mother and children. All of them are low threshold. Our first role in the complex drug care system of Frankfurt is to provide most of the injection places. Frankfurt has four safe injection rooms, and Niddastrasse offers 50% of all injections. We are open twelve hours a day, six days a week. Our second main task is to run the largest needle exchange in Frankfurt. About 80% of all syringes and needles are changed in this facility. The Frankfurt situation is a special situation what you can not compare to other cities, because we have so many different programs in a very small area. Programs would look different in other cities without all the side offers, and that is why Cafe Fix don’t have to offer an injection room, and because of Cafe Fix we don’t have to offer food. If people come in and ask for food or social workers, we say it’s

Konsumraum Nidda 49

photo: www.konsumraum.de

HCLU: Do you have social workers?

Josch Steinmetz: We have social workers but mostly not for the classical counselling. It is not our first goal. Most of the people we see want the safe clean injection. At the moment. But sooner or later, some sooner some pretty late want something else. But that is usually not a topic for the first day. We have social worker for that case, but mostly the people who work in this place are students with a part time contract. We have counselling and a very low threshold medical care three times a week. Now we also have a hepatitis campain so we can make blood screening and vaccination for hepatitis A and B, for free of charge. Last month we reached about 350 people with that campain, and an injection room is a good place to reach a huge amount of people, to reach people whom other services do not reach. We see people who inject every day during the whole week, but we also see orthers who just came to the needle exchange and move to another area. These people very often have no connection with the drug help system, and we are their first contacts. We see a very different group of people. We see about three thousand different people a year just in this place.

HCLU: What is the daily avarege of visits?

Josch Steinmetz: We have 250 injectors a day and at least this many people come for the needle exchange.

Konsumraum Nidda 49

photo: www.konsumraum.de

HCLU: How many people can inject at one time?

Josch Steinmetz: Twelve. That is the amount that makes sense. It is absolutely needed that minimum one staff is present in the room at the time of injecting to make shure that the legal rules are kept, and the reaction is very fast in case of overdose. If you have more than 12 people it could go worse.

HCLU: What is the minimum amount of places?

Josch Steinmetz: One. That is the minimum.

Sterile injecting paraphernalia

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Do you have medically trained staff or you call the ambulance when an overdose happens?

Josch Steinmetz: Everybody is trained in drug related first aid. And they are very good in that. We have all we need, we have a breathing bag, tubes to put in the mouth and an automatic defibrillation machine.

HCLU: Is it necessary?

Josch Steinmetz: No. But we have it, because the city bought us one. We never had to use it, because we are quick. The most important thing is the breathing bag. The pulse measuring machine is also very usefull. In avarage, every second day we have an overdose, so we are very well trained in managing that. Sometimes much more than professionals, because they don’t have to breath so often. We are good in breathing but if we start with a first aid and we don’t see a very positive difference in a minute, than we call the ambulance. This connection is working very good because they know that if we call, than the person is still there, the person is alive and it is really a serious situation. So they come very fast. Sometimes they only come to inject narkanti. We also have it here but we are not allowed to use it, only if some of our doctor staff is present. In emergency situations, when I decide that maybe the ambulance comes too late, there is a legal way for me to use narkanti. In fact if you make a good breathing job, you can breath a person for hours. Of course it is better to get them back sooner than later, so we call the ambulance and sometimes the people are alright before they arrive, sometimes not. 50 percent of the cases we handle by ourselves, and in 50 percent we call professionals. And that works fine, we had no dead person in all that years. In ten years we had 2269 emergencies in the injection room and nobody died. On the street we found 743 persons since 1995 and about 10 or 15 died, because we were too late. An overdose is a very simple emergency in the medical sense, but if you don’t do anything people die very easily. This is one of the most important thing about an injection room that the reaction is very quick in case of overdose. The other important matter is that the used syringe does not leave the place. The used syringe is just a few minutes on the air, than we make a change and people can leave the place with a new syringe. And safe injection rooms work well in overdose and HIV prevention.

One of the twelve seats

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: What is the history of injection rooms in Germany?

Josch Steinmetz: There are also big differences between german cities. There are cities who don’t even think about this even though they also have this problem, like in Bavaria. They are also very close to this state and people from Bavaria come to this area to inject. Now we have discussion about drug tourism. I don’t care because I don’t make a difference and I’m shure that the HIV virus don’t make a difference.

HCLU: I read in the EMCDDA report that some injection rooms in fact provide services only to local people.

Josch Steinmetz: Thats right. In most of the cities in Germany they do so. At the moment the only two exceptions are Hamburg and Frankfurt. But now all the cities are running out of money and politicians start to think about it. They say these people came to Frankfurt, take our money, use our services, steal here and we don’t want that. They say we want the other cities to take the responsibility for them. That is a nice idea but if it does not work you have to act. Big cities have bigger drug problem and it is our responsibility to give the people clean syringes and clean places. Frankfurt is not as nice as ten years ago, politics have changed. But the history of Frankfurt is very special. Frankfurt and Hamburg started the first injection rooms and all the other injection rooms came out when it was legal in early 2000. We started in 1994, the first official injection room opened in the Eastside.

The once "needle park" today

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: How was it when it was not official? The government tolerated it?

Josch Steinmetz: Right. We had a huge open drug scene in the Taunusanlage, the once needle park, in front of the German bank. That was a special situation, with the red light district, the drug scene and the business district very close to each other. In 1992 they decided to close that needle park. At the same time the Banks supported the drug help system. This support helped to scale up sevices, a few new shelters were opened and the number of methadone treatment sites and other services increased a lot. In november 1992 the city closed the needle park and told the people to use the new services. For half of the people it worked, they went to those places, but the other half went to this area and did what they did before: they injected and slept and urinated on the street. And that moment the idea of injection rooms came up again. We had a bus in 1991-

Frankfurt Central Train Station

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: When you started, did you have a campain to inform the neighborhood?

Josch Steinmetz: We started in the Eastside in an industrial area, with no neighbourhood just factories. We started in this area step by step. There are two ways for injection rooms. One is to create the injection part in an existing program. It’s much easier because the staff already did their neighbourhood job. Or at a new place, and than you have to think about the neighbourhood. You really have to look where you locate a place like that and my personal opinion after all these years is that don’t ask the neighbourhood and don’t make a campain. Do it, but do it where the problem is. Than you will have the chance to tell the people, we are here to help you. We are not here to bring you more problem than you already have. There is no way to bring an injection room in a „nice area”. And this is the end of all those fancy decentralisation ideas. Everybody likes that and I would like that also because it’s nicer, small places everywhere, when every part of the city would take it’s own responsibility for it’s own people, but it does not work. If drug users walk through a nice part you have much more problems than through a place like this. We had trouble with the neighbourhood and we invited them. In 1995 we opened in the Moselstrasse, where now there’s a bar. It was sexworkers neighbourhood. The owner of our house, the houselord was also the owner of a lot of eros centers and he took care of the neighbours. He told his collegues to let us do our job. So there was no problem with the neighbourhood, only a few with sex customers and red light problems but nothing significant. We did no campain in the newspaper or anything. Here in this house it was different. We had problems with bank offices in the surroundigs, so we invited 50 or 60 people when we saw the protest starting. We gave them my telephone number and told them we do not create problems, we take problems away from you. We hired a private security just to look on the sidewalk that not too much dealing is going on, that nobody sits down and there’s not too many people at one time. It was mostly to make people feel safer. It doesn’t work perfect but it works fine. We had problems with a few people for a long time, for example the owner of another house couldn’t rent his house because it’s too dirty and too expensive, so he tried to get his money from us saying it is because of our place, but he had no chance. We had problems with the hotel over there because they said their guests don’t want that on the way to the railway station. So this place is a good location to run our services. In fact in this area a lot of people just don’t have their voice, this sounds not nice but it’s like it is. If you go to an area where people are involved in crime or don’t speak german they don’t have a voice like people have in other areas. When Frankfurt started with a heroin program two years ago in a kind of bad area, they had a huge trouble with that. I think a big city should tell the people this is a big city and big cities have special problems, and we can’t always say ’yeah we like that program, but please move to the next street where I don’t live’. There are cities where people take their neighbourhood that serious that they call you on your mobile phone when somebody urinated somewhere, and the social workers come over to discuss the pisssing person, or there’s a syringe somewhere and a social worker goes five kilometers to collect one syringe. That is not a normal thing in my understanding. So it is alright to talk to the neighbourhood in order to get a good understanding and good relation, but some things had to be done and there’s usually a risk that the neighbourhood could stop your program. There’s always a risk but don’t ask them.

An "Eros Center" in the red light district

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: We just had protests in Hungary against a simple methadone ambulance.

Josch Steinmetz: If you have a big place like this it could create problems. If we see six hundred, seven hundred people a day, you see these people going in and out. We can do our job, we can clean the place, we can look it outside, we can talk to the people don’t do that don’t throw your syringe away, we can get people to clean the whole street, we can have a private security service or work together with the police to look at the street but there’s some end somewhere. But smaller programs like a methadone ambulance for 50 to 100 people don’t have to make problems. It is better to start and when they come to ask, you tell them to call you if there’s any problem. And usually there’s not much going on and people will accept that, but if people have a chance to stop it before it starts, they are motivated to do so, so I wouldn’t give them that motivation.

HCLU: How does a safe injection room fit in the whole concept of drug care and what are the main criteria for its existence in a city?

Josch Steinmetz: I don’t say every city needs an injection room. Every city should know by themselves whether they need an injection room or not, whether the drug users need one. The social workers should know that. Among the few aspects are the number of drug deaths, the knowledge of drug use and the connection between the drug help system and the users. Whether the city’s drug help system knows their people, are they able to reach them? Have the people places to inject or not? If they live in houses, or if they live in back houses but they at least have a place, it’s a different situation. If they don’t inject in public, if they have access to clean needles and information. If you have access to them to give information, vaccines etc., than there is not a real need for an injection room in my opinion. If you have a lot of deaths in a toilet in the main railway station, if you see people injecting, if you see a lot of used syringe on the sidewalk, if people infect each other, if people have a very low knowledge about harm reduction, if you have a hard time to find these people, then these could be arguments for injection rooms, but my goal is not to get somebody from his or her good or more or less good private situation into here. My goal is that if he or she needs a needle, I would like to give them the clean syringe and the information they need, to make a safe job at home, because for me that is the normal situation. What we offer is not a normal situation. It’s the best solution in a bad time. But it should not be the end of the discussion how to use drugs. Sometimes I feel that some cities are thinking of opening injection rooms because it’s kind of like a drug help fashion, but they don’t see the point why they need it, and if they don’t see the point, they might not need it.

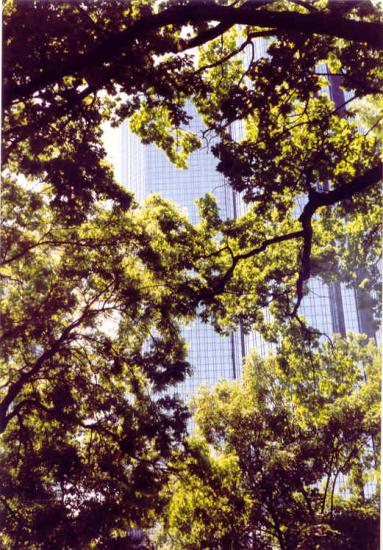

Cherry trees under the skyline

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: In Budapest there is no open drug scene, but some people go to movies or toilets of restaurants, or hidden parts of parks to inject. I wonder if opening an injection room would create public nuisance or create an open drug scene around the facility.

Josh Steinmetz: You have to take a look on the situation. For example if you have a very strong police in Budapest, and you have a huge amount of homeless drug users and you offer an injection room with just a few seats and very few opening hours, and the place is located in a dead end of a street, than it can happen, that everybody goes to this injection room, but can not get inside because it’s full, then of course you can develope a type of scene over there. And if I go to that city and I’m new in that city, for example I have trouble in Szeged and I go to Budapest as a drug user, and I don’t know anybody, the first thing I do is I go to the injection room because there I meet the people I need to meet. Of course this can happen, and if you want to start an injection room in a city and you have enough money it makes sense to start with a few injection rooms over the city, but in drug related areas. That is very very specific for every city. Every city is different. And sometimes the location, even if it is fifty meters away makes a very big difference. The experts have to know that. And don’t offer too much as long as you don’t know how it works out.

Sterile paraphernalia

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Knowing the Budapest situation, there is a minority of homeless intravenous drug users who would defenetely need such a room, although according to my knowledge it is not necessary for the majority. Could it be a solution to open a room just for the most marginalised ones?

Josch Steinmetz: Some cities do that, they say it’s not open to everybody, but restricted to members, just for homeless people or young kids for example. You make a first interview with them and you tell them, ’you are allowed to use that place for the next year’. That is one option of course. But I could not say it’s good or not. We did it different. We are absolutely open, like this open drug scene we found. The open drug scene was first and than we came, but in your situation that could be a safe start, to say O.K. we start with a few people first and see how it works, get the information and see whether we go further or not. Better than nothing, defenetely. I would say it makes sense to know the people better, because it’s a serious thing and as I remember you handle younger people than we do. Our people are 35 years and your people are sometimes younger than 18, that is a different setting. This is not a setting for young people, this is a setting for experienced drug users. I don’t want to have here a 16 year old girl.

HCLU: You send them away if they are not at a certain age?

Josch Steinmetz: Yes. It’s a different situation like in your country because here people are mostly older. The kids are mainly in Berlin. Sometimes kids come here but here kids are 17, not 13. I have the legal posibility to let them inject here if the parents signed an O.K., which is not very realistic, or the responsible youth department signed a permission. But the responsible youth departments are always home departments, so again it’s not realistic to call a small town and say ’well here is a kid from you in our place, and could you please fax a permission to inject crack?’ No way. The good thing is that there are youth street workers in our second floor, and we can call them if there’s a kid. With the youth law they have much better options than we have, they can rent a room in a hotel right in that second and give them food, and make connection with Cafe Fix. And that is good like it is. I have no problem with an injection room for kids, but than it should be different, smaller, with much more social workers because kids are looking for something different than we do.

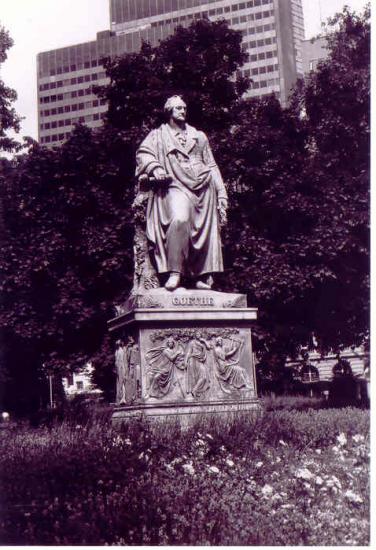

Goethe statue in the once "needle park"

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Can the aim of preventing overdose and the aim of preventing sharing needles be enough to open a room without a significan’t public nuisance and open drug scene?

Josch Steinmetz: So you are looking for arguments to open one?

HCLU: I am trying to clarify the major pro and con arguments. I am trying to understand all the aspects of the necessity and functionality of a safe injection room in a given setting. What is a situation when it is necessary or what are the alternatives. And if there is a need in a city and it may be usefull in preventing overdoses, public nuisance and disease transmissions, what are the basic criteria it has to fulfill in order to achieve its goal. Like I think if it does not have the proper capacity or opening time to cover enough injections, it may only be half measure.

Josch Steinmetz: Or, it’s like a training center. If you say I want to make HIV prevention in an injection room and people do one out of a hundred injections in your room and 99 somewhere else, you can still say that in our place they see how it works safer and we can hope they will also inject safer somewhere else. But that is more a theory, it doesn’t work like this in the reality. You can use that argument but I’m not a big believer in that. Although for some people we see changing in user behaviour in years. Thats also a result of the injection room work.

The Opera in front of the once "needle park"

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: But it is also possible to tell people safer using techniques in low threshold services, without having an injection room.

Josch Steinmetz: The big difference is that if we both talk about that, and I’m a user and you are a social worker I say of course I will do that, but you see me later doing it another way and I will say well I like it like this. So there’s a big difference betwen talking and the real action. So that can be an argument for an injecting room. Same thing with overdoses. Every drug user is an expert in handling overdose. Every drug user tells you he saved tons of lives.

HCLU: With salty water for example.

Josch Steinmetz: And all that stuff. But when you see how they act there, it’s completely different than their talking. There’s a very low knowledge about it. But everybody thinks he is an expert. So if we have an overdose eleven other people see how you handle it well, and that is very hard core education. It’s also a good argument saying, if we don’t have a contact center at the moment, we should not think about an injection room. So I would say contact center first, and there listen to the people where the real need is, and if they say I don’t need your müzli or your apple or your brochures, I need a place to inject, than you can think about that. And if people more or less inject in public, behind the tree in a park or in toilets, there’s some argument for that of course.

Garbage can for safe disposal

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: How about not reaching enough people with such a program?

Josch Steinmetz: Mostly it’s never enough, because people have to inject by night and in the weekend. When we started it was only in one city, and now there are many german cities with injection rooms. Every new injection room makes it easier for the next city to open one. There’s something else too that you have to consider. If you have a nice running contact center with a nice atmosphere, where everybody knows each other, if you start an injecting room there, the spirit of the program will change completely. And everything will focus on the injecting. And you really should think about it if you want that. It does not make the world nicer, defenetely not. It’s nice from you to think about that because people talk about that need and you want to help them, but it’s a big difference. If you are 95% social worker and 5% policeman now, you do the room and you will be a 50-50%. Social work part shrinks, and you always have to kick people out, whatch that there’s no dealing, because even the nicest people try to get stuff if they don’t have, and sometimes it’s hard for a social worker to have this discussion, to kick people out, think about security all the time, and that hurts. We would say the people like us very much, but not as much as in the good old needle exchange times. Of course we try to handle everybody with respect, but we also have so many problems to handle, and it’s not nice every time. We opened one and a half hour ago and we called the police two times already and it’s a peaceful day today, not a busy one. You don’t have to do that if you just make a needle exchange where there are not so many rules.

HCLU: I would be interested in the basic rules of this place.

Josch Steinmetz: The rules are pretty easy, mostly no sharing in any kind, no dealing, no active helping in injecting, that means no injecting each other and you have to be 18 years old or older. You may not be in methadone treatment, but that is a political rule. There are some but if they tell me they are not, I don’t know it better. It’s a political aspect not a help aspect. And there are special rules, no violence, no steeling, no walking around with an open needle, no injecting on the toilet etc. The main rule is no sharing any kind of drugs in any way.

Rules

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Do You have any quality checking?

Josch Steinmetz: No we can’t. When they come in we have to take a look on the drug so when someone comes in signs the contract with the rules, they give us their number (a code made out of their name) and we write down the drug he is taking. We can’t say it’s good coke or it is not crack, but we have to look to make shure they have something. We can’t make a quality check because if we give their drug to someone to check we can’t give it back. It would be nice though.

HCLU: Would it be possible to take a little amount of their drug and check it and tell the results?

Josch Steinmetz: It takes too much time and mostly it’s the same stuff. Sometimes if people get scared they give us their stuff and we have the contacts to test that and it’s the same every time. For me real testing would be to go to a machine and say, today it’s like this and now I know how to use it. We don’t have such a machine.

HCLU: Do you have rules not to combine drugs, like heroin with cocaine?

Josch Steinmetz: You can use mostly what you want, but you can’t smoke crack and you can’t inject the rest of the crack pipe, because it’s metal stuff inside, but you can inject and combine mostly everything. We also have the right to say ’stop now, it’s too dangerous, you are too far away, too loaded’. You are allowed to snore heroin, to smoke heroin, to snore cocain. You are not allowed to smoke crack at the moment.

HCLU: Last year when I was here there was a crack smoking room in the city.

Josch Steinmetz: Yes. In my opinion there’s not real need for that, but the cities department wanted that. It’s a tradition, once a year you have to open something new to get on the papers and to show progress. You can smoke nearly everywhere. It takes a second, and safer use of crack smoke is something different, it has more to do with eating, drinking, sleeping, and sexual behaviour.

HCLU: I did not know people also inject crack. Do they cook it with water, like heroin?

Josch Steinmetz: Yes, with ascorbine. We don’t see much powder cocaine, people just sell crack. The crack smoke is going a little bit down, and now the heroin use and benzodiazepine, rohypnol use increases. It seems we are over the edge of the crack wave. Because of different reasons, because people are sick of it and it’s too expensive, and if people have a hard time, they start with the real need first, which is heroin. If you have extra money you take the other drug.

Moselstrasse in the red light district

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: How do you see the future of injecting rooms in Frankfurt, and in Germany?

Josch Steinmetz: The german future I don’t know. I would say there are not too many new cities coming now. It is a state responsibilty, and the states decide if they want to make a legal frame for injection rooms. Just a few states have it and most of them don’t, and I’m not shure it will happen in the closer future. I would say there’s not so many going on in future.

HCLU: How about heroin prescription? Can it somehow take over the role of consumption rooms?

Josch Steinmetz: I don’t think so, at the moment it is a research, and they are not ready with the results. I would say they try to make it as a medicine. I don’t think it will go like it goes now, because it is expensive, you need it very secure and with a doctor present all the time. I don’t think they would give us the heroin to give it to the people in the near future. It is two different ways for different people. It also makes a difference, that you have to inject heroin three times a day and methadone works once a day. Frankfurt will change in the next years defenetely, but I’m not shure which way. With the elections we may have some changes. The city has plans with this area, and it seems like they wish to decrease the services of our drug help system, maybe they will cut off one or two rooms in the future. Their other idea in the future is to serve only Frankfurt people. Im not shure if they come through with that. They wish to change the anonymous system to keep the people from other cities away.

Under the skyline in the Taunus park

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: In this case some people would not come here even from this city if it were not anonymous.

Josch Steinmetz: Thats right. Others say they are used to that, and a lot of them would give the name for sure, because they trust us, and we don’t give the name to anybody. Anyway it’s a silly discussion, it’s a kind of quality discussion, and it goes this way. Much more documentation, membership system, not for people outside the city maybe, less low threshold, probably one or two programs less. I see the future like this right now. I’m expecting a little roll back in drug policy in general, because of the economic situation, but also people are sick of the drug topic, and Frankfurt wants to be a cleaner and nicer city, and OSSIP is a part of this. We are all involved in this, every programm in this area has one OSSIP staff. The first idea of OSSIP is to get the streets clean, the second idea is to help the people getting sooner into the treatment. And we can help some people with OSSIP of course, because we have more capacity for socialwork, but most of the work is done by police. From Offensive Socialarbeit Sicherheits Integration Prevention, we are the offensive social work, and SIP is the police. They do most of the job.

HCLU: Basically they try to get the people more into the institutions.

Josch Steinmetz: Right. It is not a bad thinking. And situation on the streets wasn’t acceptable. It is a thinking of cooperation. If there are four to six big NGOs with very different history, and a different understanding and different other programs in their background, and if these services come together it is much more faster to decide which service is needed for a person. And that makes sense. We did that before in another way, but not in a that organized way.

HCLU: Do the police bring the people here?

Josch Steinmetz: No. They tell them that the injecting time on the sidewalk is over, if I see you again here I take your drug so go to the injection room. And most of the people do that. And that does not make it easier for the injection room sometimes, because there’s more pressure on the people, and we had a little bit more violence in the injection room because of OSSIP. That is another side effect. When we are full and have to push people back. But that is a political thing, everybody wants it, so we are involved in that. That is the last year’s topic for the papers. The year before it was the crack smoke room, the year before that was the heroin trial. One year one program. That’s how it works in politics. The money they gave us for the OSSIP, they took it from us before, by cutting our programs. Before OSSIP we had seven days a week open, now we have six days plus OSSIP.

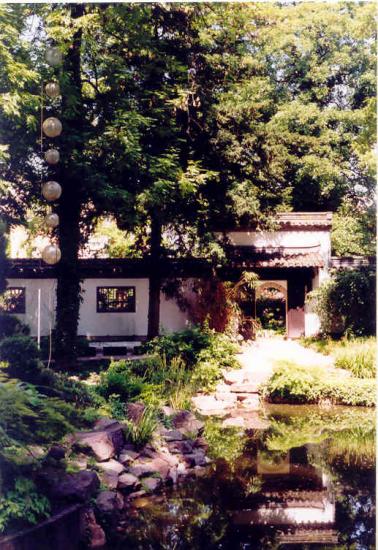

A tiny japanese garden in Frankfurt

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Well it is still better to come up with progressive ideas than circling around prohibitionist ideas like in Hungary.

Josch Steinmetz: Yes it is right that the Frankfurt way is nicer, but that doesn’t mean that they have a bigger heart or another social attitude.

Used ampulles of Twinrix

photo: István Gábor Takács

HCLU: Still, at least they give you the money. Finally should we talk about your hepatitis campain?

Josch Steinmetz: We started last august because we found a funder for the campain, it’s really bad we don’t get other money for vaccination. In my opinion the health department or the health insurance should be responsible for that. Our director from IDH is really good in finding money even in hard times. Our vaccine campain started last august. We called the people with flyers, and the first weeks we had five times a week for two or three hours to take blood and give the first shot of Twinrix. When they came for the results we gave the second shot twinrix when it was needed. At the moment we reached 365 people with that, from this we lost some people, and one third is too late to vaccine. But we also have completely finished people now, some finished just with A or B. These are real results, it’s representative, really hard data. It turned out to be a really high level of Hepatitis C, between 70 and 80% as high as we expected, a little less B and a little less A and 5% of HIV. It is also a problem that experts don’t think about A. Many people don’t want to know that you can have a big problem if you have a C and get A, so it is better to vaccine for A and B. It is easy to do it. Until the middle of the last month, we reached 355 people, from this 335 gave us their blood, and from this 236 hepatitis C, 156 B,

May 2005

István Gábor Takács

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union